Originally published in The Chronicle of Mentoring & Coaching, October 2019.

Education is the path toward upward mobility. Yet it is education plus social class that may determine the type of job a person is able to get after graduating from college. Obtaining a college degree is simply not enough to ensure that first-generation college students (FGCS) are able to find professional success and achieve upward mobility. FGCS face additional barriers to career success, including limited social capital. Social capital is represented by a social network of helpful connections. These connections lead to important resources and helpful information. Student mentoring can be enhanced by understanding the role that social capital plays in students’ success and upward mobility. There is an information gap, that researchers have called a lack of social and cultural capital, which may explain why some historically underrepresented students struggle to adapt to college life and beyond. Students can compensate for this informational gap by actively seeking advisors and mentors, also known as institutional agents. Institutional agents can provide the missing information that parents of FGCS are not able to provide to their children. Peer mentors who acquire social capital can model to their peers how to build their social capital. This paper will present and discuss a case study. Cal State Fullerton’s Latino Communication Institute (LCI) has had success in mentoring FGCS to become workforce competitive by building their social capital.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Bourdieu (1986), whose work focused on social stratification and social reproduction, was one of the first sociologists to write about social capital. He explained social capital as social, resourceful relationships based on mutual group recognition (Bourdieu, 1986). For Bourdieu (1986), group recognition is key. Membership must be recognized by the group. Bourdieu (1986) states that to persist and exist, the group needs to come together through events. Coleman (1988) points out three forms of social capital: obligations and expectations, information channels, and social norms. The relationships with institutional agents are central to the social capital framework because it is institutional agents who can offer vital resources to low socioeconomic youth (Stanton-Salazar, 2011). Stanton-Salazar (2011) suggests modifying Bourdieu’s definition of social capital which stresses mutual group recognition into this new definition of “resources embedded in social structure – and in the possibility of acting counter to the structure allowing for counterstratification” (p. 1085). This revised definition opens up the possibility that social capital is not exclusive to the upper class, as Bourdieu suggested, but can be embedded in the process of empowerment. Institutional agents motivated by social justice can go counter to the established social structure and can ‘alter the destinies’ of low socioeconomic status youth. For Stanton-Salazar (2011), empowerment social capital is what happens when an institutional agent of higher means helps a low-income student.

CONTENT

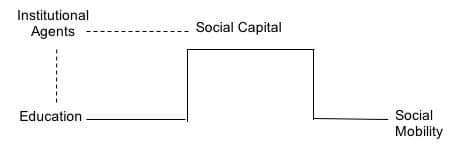

Education is the path to social mobility (Bourdieu, 1984). However, education alone does not guarantee social mobility (Boudon, 1986). A little-discussed truth in academia is that many recent college graduates are underemployed. Bourdieu (1984) calls it diploma inflation, the disparity between the educational promise (aspirations) and the opportunities the diploma offers. Roughly, 43% of college graduates are underemployed in their first job (Burning Glass Technologies and Strada Institute for the Future of Work, 2018). The first job after college graduation can have an impact on one’s future career (Burning Glass, 2018). Society offers a false promise, especially to FGCS, that a college diploma guarantees a good- paying, career-relevant job. According to Boudon (1986), education plus class is what ultimately influences what type of job a person gets. Institutional agents can teach FGCS how to build social capital to help them avoid underemployment and achieve social mobility. Figure 1 illustrates how institutional agents can help enhance FGCS educational experience and social mobility by helping them build social capital.

Figure 1. Institutional agents can help FGCS build social capital

Cal State University, Fullerton (CSUF), the largest university within the 23-campus California State University system, is a Hispanic serving institution with a 41.5% Latino student population. CSUF has a proven record of advancing the life outcomes of FGCS and Latino students, as evidenced by the fact that CSUF is first in California and second in the nation for the number of degrees awarded to Latinos. The College of Communications at CSUF graduates the most Latinos with a degree in Communications in California and is ranked second nationally. The Latino Communications Institute (LCI) compliments the work of CSUF by helping students secure a job that will create social mobility for them and their families. The mission of the Cal State University, Fullerton is to serve as a career development and employability program for students interested in working in the Latino market. This co-curricular program supports communication students in developing cultural competency in the U.S. Latino workforce through relevant courses, research, and a broad spectrum of educational opportunities. The Institute incorporates three pillars: workforce preparedness, curricular and co-curricular programs that enhance students’ Latino cultural competency, and research. In the six years since its formation, the LCI has learned a great deal about how to help FGCS build social capital to secure relevant jobs and achieve upward mobility.

The LCI helps prepare the next generation of bilingual, bicultural English-Spanish communicators through culturally responsive curriculum. This includes a “Spanish for Hispanic Media” professional certificate, immersive research in the Latino marketplace, partnerships with Spanish-bilingual media, faculty experts, and industry professionals. The LCI has a track record of coaching FGCS to become competitive in the workforce by not only focusing on coursework, but also obtaining career-relevant experience and growing their network of peers and professionals. Established in 2013, the LCI has focused on the social capital empowerment of the students and created a pathway for social mobility for students and recent graduates. The following section provides the definition of social capital and identifies three forms of social capital, which the LCI incorporates in its student mentorship.

Social Capital

Coleman (1988) identifies three forms of social capital: obligations and expectations, information channels, and social norms. Obligations and expectations are transactional favors that earn credit slips; one does a favor for someone and, due to trust in reciprocity, has the expectation they can call on a favor later (Coleman, 1988). Information channels are relationships that offer helpful information (Coleman, 1988). Lastly, social norms expect group members to act in the interest of the group and forgo self-interest (Coleman, 1988). Thus, social capital are social structures that adopt norms and trust to facilitate coordination and cooperation for mutual benefit (Putnam, 1993). Putnam (1993) writes that where one lives and whom one knows determines the social capital one can draw on. Because social structures tend to remain segregated, a challenge then becomes how to make social capital accessible to low socioeconomic status individuals.

Coleman (1988) identifies families deficient in social capital as those with the physical absence of adults or those with weak relationships between children and parents. The most prominent element of structural deficiency in modern families is the single-parent home (Coleman, 1988; Putnam, 1993). It is important to note that the lack of parents’ college education relates to cultural capital, not social capital. Nevertheless, parents’ social relations influence their children’s’ social capital. For families who have moved often, the social ties that constitute social capital are broken at each move (Coleman, 1988). For example, immigrant moving to a new country would tend to have limited social capital. Language barriers would inhibit social capital as well.

The chasm between the dominant culture and that of underrepresented students’ culture creates an information gap (Pascarella, Pierson, Wolniak, & Terenzini, 2004). Educational researchers have identified this information gap as the historically underrepresented students’ lack of social and cultural capital (Pascarella et al., 2004). Critical race theory researchers agree that historically underrepresented students do not lack cultural capital, but instead bring with them their cultural capital different from that of the dominant culture (Strayhorn, 2010; Yosso, 2005). Low socioeconomic status students can compensate for this informational gap by actively seeking advisors and mentors, or what Stanton-Salazar (2011) calls institutional agents.

LCI, teaching FGCS how to build social capital

The LCI recognizes that FGCS often experience information gaps that negatively impact their workforce competitiveness. One of the ways the LCI builds social capital is by advocating to key employers on students’ behalf to help place students in paid internships as well as help recent graduates land entry-level jobs in their field. It’s not that easy to get that first break after college, especially when one has limited social capital. LCI’s founding partner Casanova//McCann is a good example of the important role an employer can have in preparing college students for their first career job after graduation. Casanova has welcomed dozens of interns to their firm and hired many recent college graduates. As part of the LCI’s two-year partnership with the PRSA Foundation, we placed Latino PRIME Scholars in top PR agencies such as Edelman, Weber Shandwick, Hill + Knowlton Strategies, and Ogilvy. In the newsroom, where Latinos are underrepresented, the LCI works to identify small media markets that are willing to give a chance to recent graduates. Telemundo in Oklahoma, for example, has opened its doors to several of the LCI alumni. The advocacy that we do on behalf of the students is paying off. LCI has alumni working in Texas, Philadelphia, Oregon, Arizona, Washington, D.C., New York, and California. The LCI has also increased its presence in the entertainment industry in Los Angeles and New York with alumni working at Creative Artists Agency (CAA), NBCUniversal, Paramount Pictures, and Sony Pictures Entertainment.

As part of its work, the LCI identifies barriers that inhibit academic and professional success. For example, one barrier that LCI has been able to identify is familial pressure to stay local after graduation. For most of our journalism students, initial career success is predicated on relocating out of the Los Angeles market (the second largest media market in the nation), in order to start their careers. However, this proves problematic as Latino parents expect that their children will choose to live nearby after graduation. The LCI mitigates this barrier by providing culturally appropriate advocacy that helps parents/families understand the opportunities made possible through relocation. Beyond advocacy, LCI also addresses the specific needs of students and graduates by offering emotional support to assist with the transition into a predominantly white-dominant industry and possibly out of the region. Often referred to as “family” by student participants, the LCI is a valuable network that becomes an essential part of students’ social capital.

The LCI is a virtual Institute comprised of over 150 students and alumni. Three empowering institutional agents, faculty and staff, lead the work. The alumni not only continue to benefit from being part of this community but also act as peer mentors to each other and to students. The group remains connected by a closed Facebook page where job postings and other opportunities are shared on a weekly, if not daily basis. An alumni event takes place every year. Each semester the LCI has a kickoff and wrap-up event. All three of Coleman’s (1988) forms of social capital are evident in the LCI. The students and alumni consistently share job opportunities, and other helpful information. Students must invest in building relationships to get full advantage of the social capital the group offers. A culture of paying it forward has been established, evident by alumni’s financial contributions to the Institute and their willingness to peer mentor others in the group. Alumni, some who graduated five years ago continue to be heavily invested in the Institute. They are grateful for the social capital they earned through the LCI and embrace the idea of paying it forward. As Coleman (1988) suggests, as long as the established relations provide benefits, the actors will continue the relations. The following section explains the important role that resourceful institutional agents can have to help FGCS learn how to increase their social capital not only as students but throughout their life.

Institutional Agents

Stanton-Salazar (2011) defined institutional agents as non-family members with relative high-status, able to offer social and institutional support to an adolescent. The degree that institutional agents are effective in empowering youth depends on the “resourcefulness of their own social networks, as well as their orientation toward effective networking” (p. 1068). Institutional agents are part of the institutions’ supportive ties, which offer resources and social support to youth to ensure their active participation in the institution (Stanton-Salazar, 2011). The relationships with institutional agents are central to the social capital framework because it is the institutional agents who offer the vital resources to the youth (Stanton-Salazar, 2011).

In college, institutional agents can provide the missing information that parents of FGCS are not able to offer to their children. Institutional support, programs, and resources available to students can also mitigate this information gap (Stanton-Salazar, 2011). Although relationships with institutional agents are of value to all students, they become crucial for students of color (Watson et al., 2002). Studies have shown that “marginalized students are more successful at navigating the cultural, psychosocial, and intellectual college terrain when they benefit from key forms of assistance from institutional agents” (Deil-Amen, 2011, p. 58). However, historically underrepresented students may lack the necessary confidence to become engaged with their institution and to seek help (Bensimon, 2007).

Stanton-Salazar (2011) presents three ideas concerning institutional agents. First, for youth to prosper, a supportive and resourceful network of mentors, socialization agents and institutional agents is needed, as well as social activities organized within this network. Second, for many youth, especially those from working-class families, it is a challenge to create a supportive network of nonparental adults (Stanton-Salazar, 2011). Third, although social stratification tends to keep underprivileged youth in a low socioeconomic status, interventions help selected youth build the trusting networks they need to succeed. These interventions are what Stanton-Salazar (2011) defines as empowerment.

While social stratification regulates access to social capital (Bourdieu, 1986; Stanton-Salazar, 2011), those of low socioeconomic status do find ways to empower themselves, often with the help of institutional agents. Nevertheless, as a norm, low socioeconomic status youth do not know how to access well-resourced institutional support. When they do, it’s through interventions such as special educational programs where students become involved and build relationships with committed institutional agents. Stanton-Salazar identifies three significant challenges for students from historically underserved communities to develop supportive relationships with institutional agents. First, differences in gender race/ethnicity, class, and cultural perspectives when the institution does not show commitment to diversity and equity (Stanton-Salazar, 2011). Second, FGCS tend to be more dependent on non-familial institutional agents; therefore, trust and solidarity are vital in these types of relationships. Third, potentially eligible agents may be hindered by bureaucracy and personal agendas that do not value efforts to offer low socioeconomic status youth empowerment social capital.

Stanton-Salazar (2011) introduces the concept of “empowerment social capital”, allowing for the possibility that institutional agents can break the social reproduction theory and redistribute resources “in the service of social justice and counterstratification (p. 1085). Through social capital empowerment youth learn to collaborate with others, to exercise interpersonal influence, to act politically, to confront and contest oppressive institutional practices, to make tough decisions and work to solve community problems, to organize and perform complex organizational tasks, and to assume democratic leadership” (Stanton-Salazar, 2011, p. 1093). It is not enough to empower youth to do well academically and to build social capital. It is also essential to empower youth engage in meaningful social change.

CONCLUSION

Almost half of recent college graduates are underemployed in their first job after graduation. FGCS, especially, struggle to start their career. For FGCS, social capital can make a difference between underemployment and social mobility. Social capital is represented by social, resourceful relationships based on trust in reciprocity. This social network of helpful connectors support each other by sharing valuable information (e.g, job leads). Institutional agents can and should teach FGCS how to build social capital to achieve social mobility.

The LCI has been successful in creating a social network that helps FGCS become workforce ready and able to secure internships and employment with top employers. The Institute does this with the help of resourceful institutional agents who provide vital information to students and alumni. Consistent gatherings keep the LCI network connected and strong. Alumni are asked to pay it forward by mentoring peers and students, which makes the network more powerful and effective. The LCI alumni stays engaged and involved because they see a benefit from being an active member of this network. Job postings are often shared within the group by alumni who act as references for each other. As the alumni continue to move up the ladder, the network becomes even more resourceful. Often referred to as a family-type community by student participants, the LCI is a valuable mentorship network for students and alumni.

REFERENCES

Bensimon, E. M. (2007). The underestimated significance of practitioner knowledge in the scholarship on student success. The Review of Higher Education, 30(4), 441-469.

Boudon, R. (1986). Education, Social Mobility, and Sociological Theory. In Richardson, J.G. (Ed.), Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education (261-274). New York, NY: Greenwood Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction: A social critique of the judgement of taste. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1986). The Forms of Capital. In Richardson J. G. Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education (241-58). New York, NY: Greenwood Press

Burning Glass Technologies & Strada Institute for the Future of Work (2018), The Permanent Detour: Underemployment’s Long-Term Effects on the Careers of College Grads. Retrieved from: https://www.burning-glass.com/wp-content/uploads/ permanent_detour_underemployment_report.pdf

Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital. The American Journal of Sociology 94, S95-S120

Deil-Amen, R. (2011). Socio-Academic integrative moments: Rethinking academic and social integration among two-year college students in career-related programs. The Journal of Higher Education 82(1), 54-91.

Pascarella, E., Pierson, C. T., Wolniak, G.C., & Terenzini, P. T. (2004). First- generation college students: Additional evidence on college experiences and outcomes. The Journal of Higher Education, 75(3) 249-284.

Putnam, R. D. (1993). The prosperous community: Social capital and public life. The American Prospect. Retrieved from: https://prospect.org/article/prosperous-community-social-capital-and-public-life

Stanton-Salazar, R. D. (2011). A social capital framework for the study of institutional agents and their role in the empowerment of low-status students and youth. Youth & Society, 43(3), 1066-1109.

Strayhorn, T. L. (2010). When race and gender collide: Social and cultural capital’s influence on the academic achievement of African American and Latino males. The Review of Higher Education, 33(3), 307-332. doi:10.1353/rhe.0.0147

Watson, L. W., Terrell, M. C., Wright, D. J., Bonner, F. A., Cuyjet, M. J., Gold, J. A., Rudy, D. E., & Person, D. R., (2002). How minority students experience college. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing.

Yosso, T. J. (2005). Whose culture has capital? A critical race theory discussion of community cultural wealth. Race, ethnicity and education, 8(1), 69-91.